Article content

Loaves that are deliberately underbaked, sacks stuffed with enzymes and additives (so-called E-numbers) in warehouses, and old bread ground up into the dough.

You can find all of this in an average Czech bakery. Over the last twenty years there has been a dramatic decline in the quality of traditional Czech bread. Domestic bakers have largely abandoned the traditional method of production and instead of making loaves from sourdough, flour and water they prepare them from pre-mixed blends and deactivated industrial yeasts.

Bread

Original recipes are now kept by only a small percentage of businesses. So bread may still look the same as before, but the shape, color and taste of the loaves are driven by enzymes and various “E-numbers.” Thanks to them, bread production has been shortened by more than half the time. “Today bakers replace time with enzymes and other additives,” says Josef Příhoda, who has devoted most of his life to bread production at the University of Chemistry and Technology.

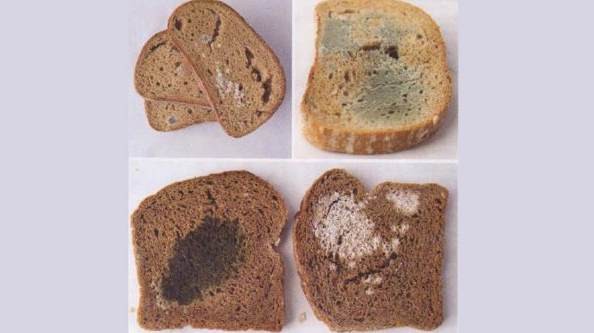

“Besides the fact that the natural taste and aroma have disappeared from bread, it decays much faster. A moldy crumb is not unusual even after three days. Yet twenty years ago food standards determined that bread had to remain edible for four days. Today the “shelf life” for most breads has shrunk to twenty-four hours after baking.” says Associate Professor Josef Příhoda from VŠCHT.

Processing of bread in the Czech Republic

A common practice in Czech bakeries is adding soaked unsold loaves into the new dough. “Old bread can easily make up a tenth of the volume of the new one,” confirms Vladimír Doležal from the Czech University of Life Sciences. It is also not at all uncommon to deliberately underbake bread. It is then softer and customers consider it fresher. “A lot of people choose bread by feeling it and pick the soft one, because for them that is synonymous with fresh. Well, if you bake the bread for forty-five minutes instead of fifty, it will be softer to the touch. And this is precisely what some bakers do,” explains Jaromír Dřízal from the bakers’ association.

Bakers with sacks of premixed blends and loaves that go moldy in three days, but do not represent the only villains in this story. Others are supermarkets. They push bakeries to the lowest possible prices, charge them various fees and, through contracts, force bakers into rather unusual behavior. Czech bread is in decline…